The Secret To Perfect Plyometric Training

- fit4training

- Sep 27, 2017

- 3 min read

So often I walk into a gym and see fitness trainers doing ‘plyometric’ type activities with their clients… But usually, something doesn’t quite seem right about what they are doing. Yes, their client is working hard… but to what end? What is the purpose of this slow, painful looking, box-jumping, leaping and bounding? I’m not entirely convinced that the trainer always really understands why they are doing what they are doing and how to do it most effectively.

So firstly, what is plyometric training?

Plyometric training is a combination of sheer strength combined with super-fast speed of movement… But that is not all. Pure plyometric training also requires that the muscles being worked are pre-stretched (under tension/loading) immediately prior to their forceful concentric contraction. This pre-stretching causes what is known as the ‘Stretch-reflex’ to occur. This is a mechanism that adds more force to a muscle contraction than if it was contracted without the pre-stretch.

Think of it like this…

During most movements, to be most efficient, there are 3 distinct phases:

The ECCENTRIC phase lengthens the muscles controlling the moving joint

The AMORTISATION phase is when those muscles dynamically stabilise the joint and prepare for the next phase

The CONCENTRIC contraction of the muscle causes the explosive movement to occur

As an example…

In a standing broad jump, to jump as far as possible, the following movement pattern should occur:

The jumper begins to crouch down (hip, knee and ankle flexion) by eccentrically lengthening his/her leg muscles

The jumper reaches the depth of their crouch and then very quickly stabilises their joints during a momentary pause ready for…

The concentric explosive extension of the legs in order to jump as far as possible.

So what could go wrong?

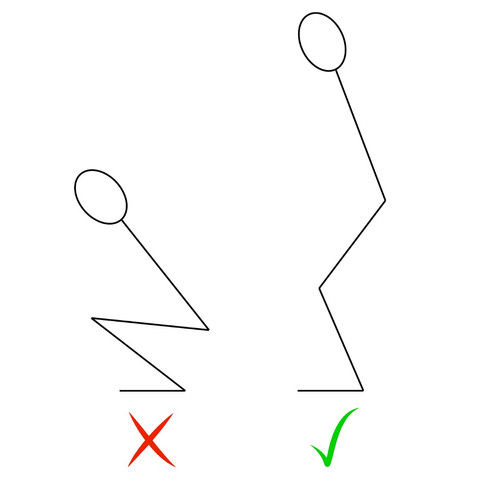

Sticking with the same example broad jump, fitness trainers often make the following mistakes with their client’s technique:

The eccentric phase is too deep taking joints into too much flexion and lengthening muscles far too much. The consequences of this are that from deeply flexed positions, we cannot move our limbs quickly, therefore our power output is limited

The amortisation phase is too long. The consequence of this is that the ‘stretch-reflex’ is much weaker, again causing less power production

So how do we stop making these mistakes?

Firstly, think about the joint angle at which we can optimally move quickly and with force. This angle should be a relatively open angle ie, the joint should be roughly 2/3s through its extension – not quite fully extended. Of course, we are not all the same, but generally, with practice, people will find the correct joint angles for themselves given their own individual strength, lever length, bodyweight etc.

Secondly, we should minimise the amortisation duration to as shorter time as possible. This means that you should focus on transferring from eccentric to concentric muscle actions as quickly as possible.

An example of both of these in action, is watching an Olympic weightlifter as they ‘jerk’ above their head in a clean and jerk lift. They will firstly flex hips, knees and ankles into a shallow squat – no more than a third into flexion. They will then very quickly change the vector of the force upward in order to fully capitalise on the stretch-reflex. Despite lifting weights above 200kgs, these athletes are so well trained that their amortisation phases are over in the blink of an eye! Watch the following video clip and imagine changing direction this quickly with 245kgs across your chest!

Dmitry Klokov - Jerk from rack

Given that the majority of sports movements (indeed life movements!) use power produced from the legs (glutes, hamstrings, quads, gastrocnemius, soleus), then this means that plyometric training should include jumping, leaping and bounding actions – all done with minimal contact time on the ground and maximum speed and force production.

Hurdle plyometrics

Is there a place for slower, deeper movements in training – well, sometimes yes. Knowing when to incorporate all aspects of plyometric and power training is a bit of an art-form.

You can learn more about it on the Fit4Training Sports Conditioning course launching in January 2018.

Comentários